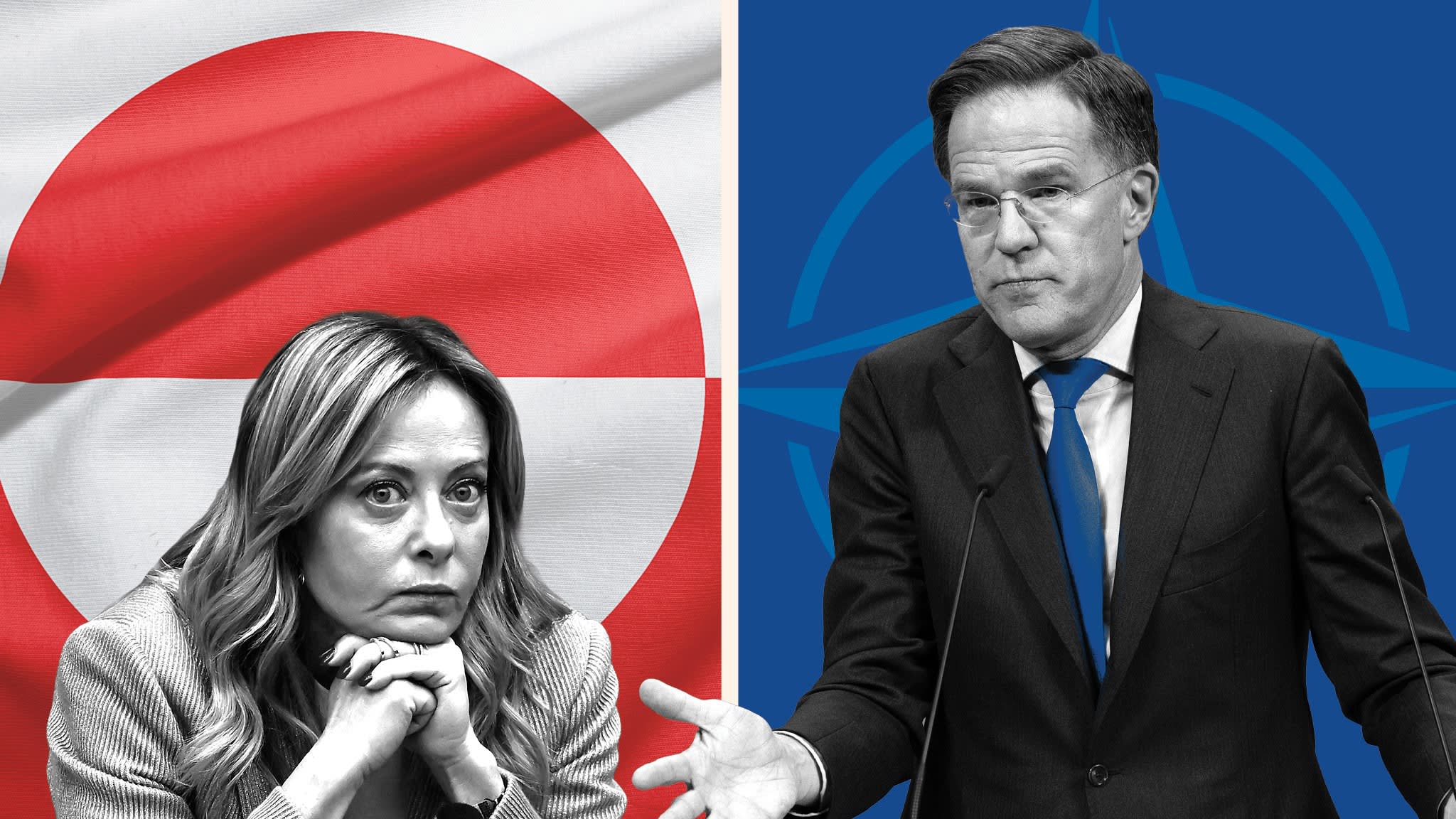

The resurgence of transactional diplomacy on the global stage has reignited a dormant but deeply sensitive geopolitical debate, casting a long shadow over the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). At the center of this tension is Greenland, the world’s largest island and a constituent country within the Kingdom of Denmark, which has once again found itself in the crosshairs of American strategic interests. As former President Donald Trump doubles down on rhetoric suggesting a renewed interest in the acquisition or heightened control of Greenland, a conspicuous silence from NATO headquarters in Brussels has sent ripples of anxiety through European capitals. This diplomatic reticence is being interpreted by many allies not merely as a refusal to engage in speculative politics, but as a troubling sign of the alliance’s fragility in the face of a potential shift in U.S. foreign policy priorities.

The geopolitical significance of Greenland has undergone a radical transformation over the last decade, driven by the dual forces of climate change and great-power competition. Traditionally viewed as a frozen periphery, the Arctic is rapidly becoming a central theater for economic and military maneuvering. The melting of the polar ice caps is opening previously inaccessible shipping lanes, most notably the Northwest Passage, which promises to shave weeks off transit times between Europe and Asia. For Washington, Greenland is the "stationary aircraft carrier" of the High North, hosting the Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule Air Base). This installation is a critical node in the U.S. integrated tactical warning and attack assessment system, providing essential radar coverage for North American aerospace defense.

However, the renewed American interest is as much about what lies beneath the ice as what sits upon it. Greenland is home to some of the world’s most significant undeveloped deposits of rare earth elements (REEs), including neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium. These minerals are the lifeblood of the modern high-tech economy, essential for everything from electric vehicle motors and wind turbines to advanced missile guidance systems. Currently, China controls approximately 85% of global REE processing capacity and a significant portion of raw mining output. For an American administration focused on "de-risking" or "decoupling" from Chinese supply chains, Greenland represents a strategic hedge of unparalleled value. Estimates suggest that the Kvanefjeld project in southern Greenland alone could potentially meet a substantial portion of the Western world’s demand for rare earths, a factor that has not escaped the notice of economic nationalists in Washington.

The silence from NATO leadership regarding these territorial overtures is particularly jarring for Denmark and its Nordic neighbors. Under the North Atlantic Treaty, the territorial integrity of all member states is supposedly sacrosanct. By failing to issue a robust defense of Danish sovereignty in the face of "purchase" rhetoric, critics argue that NATO risks signaling that the borders of its members are negotiable if the price is right or if the pressure from its largest contributor becomes too great. This perceived equivocation strikes at the heart of Article 5, the collective defense clause. If a member’s territory can be the subject of a transaction, the philosophical foundation of the alliance—that an attack on one is an attack on all—begins to erode, replaced by a model where security is a commodity rather than a shared commitment.

In Copenhagen, the mood is one of quiet but intense frustration. The Danish government has consistently maintained that Greenland is not for sale, a sentiment echoed by the Greenlandic government (Naalakkersuisut) in Nuuk. Yet, the internal dynamics of the Kingdom of Denmark are complex. Greenland enjoys significant autonomy under the 2009 Self-Government Act, which grants it the right to seek total independence if its people so choose. Strategic maneuvers by the U.S. could inadvertently—or perhaps intentionally—accelerate the independence movement, potentially creating a vacuum that Washington might seek to fill with bilateral security and economic agreements that bypass the traditional NATO framework.

The economic impact of this uncertainty is already being felt in the Arctic investment landscape. While the prospect of American capital is generally welcomed, the specter of becoming a pawn in a U.S.-China-Russia power struggle is deterring more cautious European institutional investors. The Arctic Council, once a forum for peaceful scientific and environmental cooperation, has seen its functionality crippled following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. With the "Arctic Exception"—the idea that the High North could remain a zone of low tension—now effectively dead, the region is seeing a rapid buildup of military assets. Russia has reopened hundreds of Soviet-era military sites in the Arctic, while China has declared itself a "near-Arctic state," signaling its intention to integrate the region into its "Polar Silk Road" initiative.

Against this backdrop, NATO’s lack of a clear stance on the Greenland issue is viewed by European diplomats as a symptom of a broader crisis of confidence. There is a growing fear that a future U.S. administration might adopt a "mercantilist" approach to security, where protection is contingent upon economic concessions or the hosting of American assets under U.S., rather than multilateral, jurisdiction. This would represent a fundamental departure from the post-war liberal order and could force European nations to accelerate their pursuit of "strategic autonomy." The European Union has already begun to formulate its own Arctic strategy, emphasizing environmental protection and sustainable development, but it lacks the hard power capabilities to replace the security umbrella currently provided by the U.S. through NATO.

Market analysts suggest that the "Greenland question" is a bellwether for how global trade and security will intersect in the mid-21st century. If the U.S. were to successfully exert greater control over Greenland’s resources, it would fundamentally alter the global commodities market. A U.S.-aligned Greenland could break the Chinese monopoly on rare earths, potentially leading to a more stable supply chain for Western tech and defense firms. However, the cost of this shift could be the alienation of traditional European allies who view such moves as neo-colonialist and disruptive to the regional balance of power. The potential for trade friction is high; if the U.S. were to apply "America First" policies to Greenland’s mineral exports, it could lead to retaliatory tariffs or trade disputes with the EU, which is also desperate to secure its own green energy transition.

Furthermore, the indigenous perspective remains a critical, yet often overlooked, variable. The Inuit population of Greenland has a profound connection to their land and a history of navigating the interests of distant colonial powers. Any attempt to transform the island into a strategic extraction zone without the explicit and sustained consent of the local population would likely trigger significant social and political unrest. This domestic instability could, in turn, provide an opening for foreign adversaries to sow discord within the alliance, using disinformation to paint the U.S. as an imperialist actor.

As the 2024 U.S. election cycle gains momentum, the "Greenland threat" remains a potent symbol of a shifting geopolitical paradigm. For NATO, the challenge is to find a way to reaffirm the principles of sovereignty and collective security without alienating its most powerful member. The current policy of silence may be a temporary tactical choice intended to avoid unnecessary confrontation, but as a long-term strategy, it appears increasingly untenable. European allies are looking for more than just quiet diplomacy; they are seeking a clear, unequivocal commitment that the map of the North Atlantic is not a catalog for the highest bidder.

In the final analysis, the controversy over Greenland is about more than just a vast expanse of ice and rock. It is a test of whether the world’s most successful military alliance can adapt to a world where economic resources are as strategically vital as territory, and where the lines between commerce and conquest are becoming increasingly blurred. If NATO cannot find its voice on the Greenland issue, it may find that its silence has spoken volumes about the future of transatlantic unity, leaving the Arctic—and the allies who depend on its stability—in a state of profound and dangerous uncertainty. The economic and security stakes are too high for the "High North" to be left in a diplomatic deep freeze.