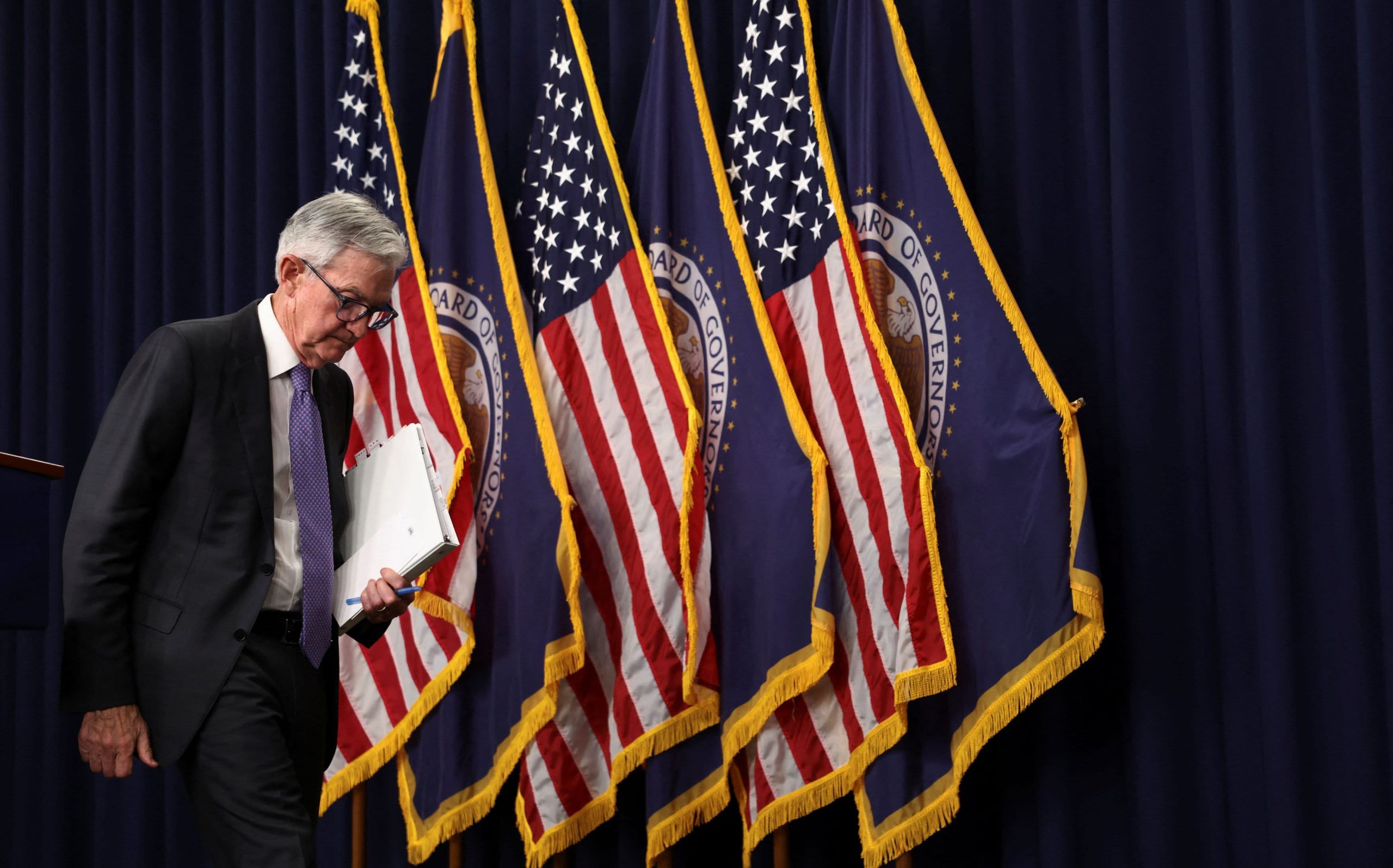

The characteristic composure of Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell at the podium has long been a stabilizing force for global markets, yet beneath the technical jargon of "data-dependent" policy lies a looming constitutional and economic confrontation. As the countdown to May 2026 begins, a singular question has paralyzed Wall Street analysts and constitutional scholars alike: Will Powell remain on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors after his term as chair expires? While his leadership of the world’s most powerful central bank is set to conclude in the spring of 2026, his underlying 14-year term as a member of the Board of Governors does not legally expire until 2028. Powell’s pointed refusal to clarify his intentions has transformed a routine administrative transition into a high-stakes chess match over the very soul of the Federal Reserve’s independence.

The silence emanating from the Eccles Building is uncharacteristic for an era of "forward guidance," yet it is strategically calculated. During his December press conference, Powell remained resolute, stating he was focused solely on his remaining time as chair and had nothing new to share regarding his future. This ambiguity has invited intense speculation among Fed watchers who are attempting to map out the future of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The stakes are not merely personal; they involve the mathematical control of the seven-member Board of Governors and, by extension, the trajectory of U.S. monetary policy in an era of heightened political volatility.

To understand the gravity of Powell’s decision, one must look at the structural composition of the Fed. The Board of Governors consists of seven members, each appointed to staggered 14-year terms to insulate them from the short-term whims of the electoral cycle. Traditionally, when a chair’s four-year leadership term ends and they are not reappointed, they resign from the board entirely, allowing the sitting president to appoint a fresh successor. This was the path taken by Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, both of whom transitioned gracefully into the private sector or other government roles. However, Powell finds himself in a historical vacuum. Not since Marriner Eccles in 1948 has a former chair considered staying on as a regular governor. Eccles’ decision to remain was born of a desire to protect the Fed from being forced by the Treasury Department to keep interest rates artificially low—a parallel that is strikingly relevant today.

The current political climate has turned the "math of the board" into a primary concern for economists. President Donald Trump, who has frequently and publicly criticized Powell’s interest rate decisions, has made no secret of his desire for more direct influence over monetary policy. The Trump administration’s economic platform relies heavily on low interest rates to reduce the cost of servicing the massive $34 trillion U.S. national debt and to stimulate domestic manufacturing. Currently, three Trump appointees sit on the seven-member board. If Powell follows tradition and departs in May 2026, the President would have an immediate opportunity to fill that vacancy, potentially securing a four-member majority. Such a bloc could, in theory, override the more cautious, inflation-focused consensus that has defined the Powell era.

The implications of a politically captured Fed board extend beyond simple interest rate adjustments. Under the Federal Reserve Act, the Board of Governors holds significant "for cause" removal power over the presidents of the twelve regional Federal Reserve banks. While the legality of firing a regional president for disagreeing with the board’s policy is a matter of intense legal debate, a loyalist majority on the board could attempt to purge the FOMC of "hawkish" voices who resist aggressive rate cuts. Powell’s continued presence on the board, even if he were no longer the chair, could serve as a vital "firewall," preventing the board from reaching the quorum necessary to enact such radical institutional changes.

The tension is further exacerbated by the ongoing legal saga of Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook. The Trump administration’s attempt to remove Cook over allegations of past mortgage fraud—which she has denied—has moved to the Supreme Court, with oral arguments scheduled for late January. The outcome of this case will serve as a bellwether for the future of the Fed. If the Supreme Court rules that the President has broader authority to remove "independent" regulators without traditional "for cause" protections, the institutional shield surrounding the Fed would effectively vanish. In such a scenario, Powell’s decision to stay or go might be rendered moot, as he would likely become the next target for removal. Conversely, if the Court upholds the Fed’s independence, Powell may feel a renewed sense of duty to remain in his seat until 2028 to ensure the institution’s long-term stability.

Market participants are watching these developments with growing trepidation. The "independence premium" is a tangible factor in the valuation of the U.S. dollar and Treasury bonds. If global investors begin to perceive that the Fed is taking orders from the White House, the credibility of the U.S. inflation target could erode. This could lead to a "term premium" spike, where investors demand higher yields to compensate for the risk of politically induced inflation. Historically, countries that have compromised central bank independence—such as Turkey or Argentina—have suffered from chronic currency devaluation and capital flight. While the U.S. economy remains the world’s anchor, the erosion of the Fed’s autonomy could threaten the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency.

Beyond the institutional mechanics, there is a profound personal dimension to Powell’s dilemma. After thirteen years on the board and eight years as chair, Powell has endured a level of public vitriol from the executive branch that is unprecedented in modern American history. Friends and associates describe him as a man who values his private life, his family, and his hobbies, including playing the guitar and golfing. At 71, he is a grandfather who has more than earned a quiet retirement. However, Powell is also a student of history with a deep sense of institutional loyalty. He views himself not just as a policymaker, but as a steward of an agency that must remain apolitical to function effectively.

Some analysts suggest that Powell’s silence is a form of "strategic ambiguity" designed to exert leverage over the administration’s choice of a successor. By refusing to commit to a departure date, he sends a subtle message: if the administration nominates a qualified, mainstream economist to replace him as chair, he will step down and allow for a smooth transition. If, however, the administration attempts to install a political loyalist intended to dismantle the Fed’s norms, Powell may exercise his legal right to stay on the board as a governor, serving as a powerful dissenting voice and a procedural roadblock to radical policy shifts.

This "Eccles Strategy" would be a double-edged sword. While it might protect the Fed in the short term, it would undoubtedly draw the central bank deeper into the political fray. A former chair sitting on the board while a new chair tries to lead could create a dual power structure, leading to confusion in the markets and internal friction within the FOMC. Critics argue that by staying, Powell would be breaking a long-standing norm that has helped maintain the appearance of a non-partisan transition. Yet, in an era where many norms have already been discarded, Powell may conclude that the survival of the institution outweighs the value of tradition.

The global context adds another layer of complexity. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) operate under different legal frameworks that provide even stronger statutory independence than the Federal Reserve. If the Fed is seen as backsliding into political subservience, it could shift the balance of power in global finance, making the Euro or other currencies more attractive to central banks looking to diversify their reserves. The Federal Reserve’s "dual mandate" of maximum employment and price stability requires a delicate balancing act that is difficult enough to achieve under ideal conditions; adding the pressure of an election cycle to the equation could make that mandate impossible to fulfill.

As May 2026 approaches, the pressure on Powell will only intensify. Every speech, every congressional testimony, and every "dot plot" will be scrutinized for clues about his future. Whether he chooses the quiet life of a private citizen or the grueling path of a "guardian of the gates," his decision will be a defining moment in American economic history. For now, the Chair remains silent, holding his cards close to his vest, while the world waits to see if the most powerful banker in the world is ready to walk away—or if he is preparing for one final, defiant stand.