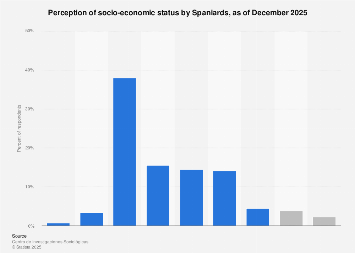

As the calendar turned to December 2025, a comprehensive survey conducted among 4,017 Spanish adults aged 18 and older, utilizing computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI), revealed a fascinating landscape of socio-economic self-perception. The findings underscore a significant concentration of the Spanish population identifying with the broad middle class, with a substantial portion placing themselves squarely within the "mid middle-class" category. This segment represents nearly two-fifths of all respondents, solidifying its position as the dominant self-identified social stratum.

The data, gathered between December 1st and 5th, 2025, paints a nuanced picture of how Spaniards view their place in the economic hierarchy. While the "mid middle-class" emerges as the largest single group at 38 percent, its closest rival, the "lower middle-class," accounts for a considerable 15.5 percent of the surveyed populace. This close proximity suggests a significant portion of the population feels positioned on the cusp of upward mobility or is actively navigating the challenges of maintaining a middle-class standing.

Beyond the immediate middle-class definitions, the "working class" or "proletariat" is identified by 14.4 percent of respondents, a figure that closely mirrors the 14.1 percent who classify themselves as "lower class." These two categories, when combined, represent a significant bloc of the population experiencing economic realities that place them below the generally accepted middle-class benchmarks. The presence of a 4.4 percent identifying as "poor" further highlights the persistent challenges faced by a segment of Spanish society, despite broader economic trends.

At the upper echelons of the social hierarchy, the perception of belonging to the "upper class" remains a relatively exclusive designation, claimed by a mere 0.7 percent of respondents. The "upper middle-class" designation, while more substantial, still represents a smaller segment of the population at 3.4 percent. These figures suggest a perception of social mobility being more skewed towards the lower and middle segments, with limited self-identification with the highest social strata.

A notable aspect of the survey results is the inclusion of categories for those who were undecided or unwilling to answer. The "Don’t know/don’t answer" group comprises 3.9 percent of respondents, indicating a degree of uncertainty or perhaps a reluctance to firmly categorize oneself within a specific social class. Additionally, 2.3 percent identified with "Other" categories, suggesting a recognition of socio-economic nuances that fall outside the provided classifications.

These self-perceptions are crucial indicators for understanding consumer behavior, political leanings, and overall societal sentiment. The dominance of the "mid middle-class" suggests a strong consumer base with moderate disposable income, likely prioritizing stability, quality, and value in their purchasing decisions. However, the significant presence of the "lower middle-class" and "working class" points to a substantial segment of the population that may be more price-sensitive, focused on essential goods and services, and potentially more receptive to economic relief measures or populist political messaging.

The relatively low self-identification with the "upper class" is a common phenomenon across many developed economies. While wealth distribution may show a concentration at the top, individuals’ lived experiences and daily concerns often anchor them in perceptions closer to the middle or working classes. This can be influenced by factors such as education levels, occupational prestige, and cultural capital, which may not always directly correlate with extreme wealth.

Economically, the distribution of self-perceived social class has tangible implications. For instance, the demand for luxury goods and high-end services would likely be concentrated among the smaller upper and upper-middle-class segments. Conversely, sectors catering to everyday necessities, such as affordable housing, mass-market retail, and essential services, would find a larger customer base within the dominant middle and lower segments.

The survey’s methodology, employing CATI, ensures a broad reach across different demographics, including those who might not have consistent internet access. The sample size of over 4,000 respondents further lends statistical weight to the findings, providing a robust snapshot of public opinion on social stratification.

Comparing these figures to broader European economic trends, Spain’s self-perception of social class distribution is not entirely anomalous. Many Western European nations exhibit a similar tendency for the majority of the population to identify with some form of middle class. However, the specific percentages can vary significantly, influenced by national income levels, the strength of social welfare programs, historical class structures, and recent economic performance. For example, countries with a more pronounced welfare state and a history of strong labor movements might see a larger proportion identifying with working-class or lower-middle-class categories, while those with more liberalized economies and a strong service sector might see a greater expansion of the middle class.

The implications for economic policy are considerable. Governments and policymakers would need to consider the needs and aspirations of the large middle segment when formulating fiscal policies, taxation strategies, and social support systems. Measures aimed at bolstering the purchasing power of the lower-middle and working classes could stimulate domestic demand, while policies supporting education and skill development would be crucial for upward mobility, potentially shifting more individuals towards the "upper middle-class" over time.

Furthermore, the perception of belonging to a particular social class can influence social cohesion and political stability. A large, satisfied middle class often acts as a stabilizing force in society. Conversely, a widening gap between the perceived economic realities of different social strata, or a sense of stagnation within the middle class, can fuel social discontent and political polarization.

The data from December 2025 serves as a valuable benchmark for understanding the current socio-economic fabric of Spain. As the nation navigates future economic challenges and opportunities, monitoring these self-perceptions will be essential for policymakers, businesses, and social analysts alike. The strength and composition of the Spanish middle class, in its various forms, will undoubtedly continue to shape the country’s economic trajectory and social landscape. The significant concentration in the "mid middle-class" suggests a potential for continued economic stability, provided that policies effectively address the concerns and aspirations of this broad demographic, while also supporting those in the lower strata and fostering opportunities for advancement.