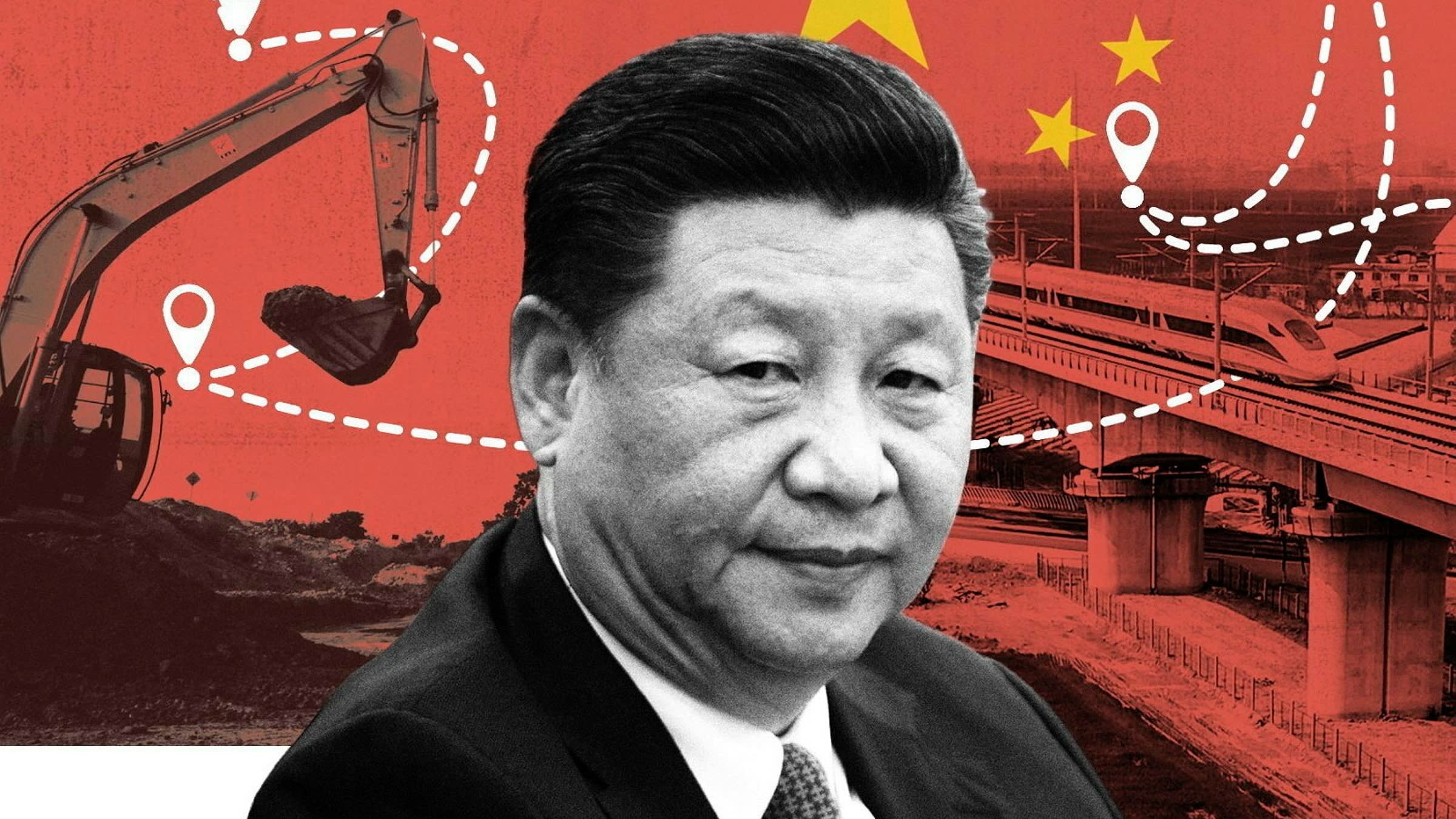

The architectural blueprint of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is undergoing a fundamental transformation, shifting from the era of "mega-infrastructure" toward a targeted, resource-centric strategy designed to underpin the next century of industrial dominance. After a decade of financing sprawling railway networks, massive deep-water ports, and expansive highway systems across the Global South, the Chinese government is recalibrating its capital outflows. The new priority is clear: securing the raw materials essential for the global energy transition, specifically the critical minerals required for electric vehicles (EVs), renewable energy storage, and high-tech manufacturing.

This strategic evolution comes at a pivotal moment for the global economy. As the world moves toward decarbonization, the demand for lithium, cobalt, copper, and nickel is projected to skyrocket. International Energy Agency (IEA) projections suggest that to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement, the world will need four times the amount of mineral inputs for clean energy technologies by 2040 than it does today. Recognizing this shift, Beijing is leveraging its refined BRI framework to ensure that Chinese industries remain at the center of the global green-tech value chain.

The financial data reflects this pivot. While total BRI engagement has seen a cooling from its mid-2010s peak—partly due to domestic economic headwinds and a more cautious approach to sovereign debt—investment in the mining and metals sector has reached record highs. In the past year alone, Chinese investments in the metals and mining sector through BRI-affiliated channels surged by more than 150% compared to previous cycles. This "resource grab" is not merely about extraction; it is a sophisticated integration of trade, finance, and diplomacy aimed at creating an unbreakable loop between foreign mines and Chinese processing facilities.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which produces roughly 70% of the world’s cobalt, Chinese state-backed firms and private entities have consolidated a dominant position. Through a series of "infrastructure-for-minerals" deals, Beijing has provided the capital for local development in exchange for long-term off-take agreements and ownership stakes in key mining assets. This model, while criticized by Western analysts for its lack of transparency, has allowed China to control approximately 80% of the global cobalt refining capacity, creating a bottleneck that Western automakers are now struggling to bypass.

The shift toward resource-linked financing is also evident in Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia. As the world’s largest producer of nickel, Indonesia has become a cornerstone of China’s "New Silk Road" strategy. However, the nature of the engagement has changed. Rather than simply financing roads to mines, Chinese capital is now flowing into massive industrial parks like the Morowali Industrial Park. These facilities are designed to process nickel ore into high-grade battery materials on-site, a move that aligns with Indonesia’s desire to move up the value chain while securing China’s supply of a critical component for its domestic EV industry.

This recalibration is also a response to the "debt-trap" narratives that have dogged the BRI for several years. Beijing has learned from the high-profile defaults and restructuring cases in Sri Lanka and Zambia. The new era of BRI financing, often referred to by Chinese officials as "small yet beautiful" projects, prioritizes smaller, more profitable, and strategically vital investments over high-risk, multi-billion-dollar prestige projects. By focusing on mining and resource extraction, Chinese policy banks like the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim) and the China Development Bank are backing projects with clearer paths to revenue and higher strategic value to the Chinese state.

Furthermore, the geopolitical landscape is driving this urgency. The United States and its allies have introduced initiatives such as the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) and the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) to provide alternatives to Chinese financing. These Western efforts are largely aimed at "de-risking" supply chains and reducing dependence on Beijing. However, China’s head start is significant. Beijing’s ability to deploy state-coordinated capital, combined with a higher tolerance for political risk in emerging markets, gives it a competitive edge that Western private-sector-led models have yet to match.

In Latin America, the "Lithium Triangle"—comprising Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile—has become a primary theater for this financial offensive. Chinese companies like Ganfeng Lithium and Tianqi Lithium, often supported by state-facilitated credit lines, have been aggressively acquiring stakes in brine projects. Unlike Western firms, which may be constrained by quarterly earnings pressure or ESG (environmental, social, and governance) mandates from shareholders, Chinese entities frequently operate with a decades-long horizon, viewing these acquisitions as national security imperatives rather than purely commercial ventures.

The economic impact on host nations is a subject of intense debate among global economists. On one hand, China’s willingness to invest in regions that the West has long overlooked provides much-needed capital for industrialization. In many BRI countries, Chinese-funded mining projects include the construction of power plants and transport corridors that benefit the broader economy. On the other hand, there are growing concerns regarding the "enclave" nature of these investments, where the majority of the value addition occurs in China, leaving host nations as mere suppliers of raw materials with limited technological spillover.

To counter these criticisms, Beijing has begun to emphasize "Green BRI" initiatives. By positioning its resource acquisitions as part of a global effort to combat climate change, China is attempting to rebrand its industrial expansion. This narrative shift is powerful in the Global South, where many nations feel marginalized by the West’s stringent environmental requirements for financing. China offers a pragmatic, if more opaque, alternative: the capital and technology to extract resources today, with fewer strings attached regarding domestic political reform.

However, the strategy is not without internal risks for China. The concentration of investment in volatile jurisdictions exposes Chinese capital to significant geopolitical and security risks. In regions like the Sahel or parts of Central Asia, political instability can threaten the continuity of supply and the safety of personnel. Moreover, as China’s own economy slows, the domestic appetite for large-scale foreign lending is being tested. The government must balance its desire for global resource dominance with the need to manage a mounting domestic debt crisis and a cooling property market.

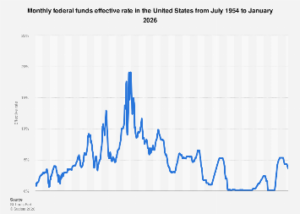

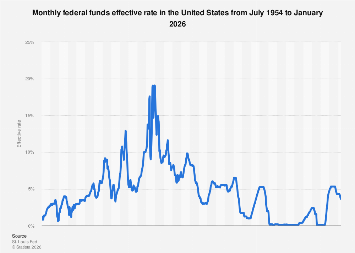

Market analysts suggest that the next phase of this resource-focused BRI will involve a greater integration of digital and financial technology. We are likely to see the expansion of the "Digital Silk Road," where blockchain-based tracking of minerals and the use of the digital yuan (e-CNY) in commodity trading could further insulate China’s supply chains from Western sanctions or the dominance of the US dollar. This would create a parallel economic ecosystem where the trade of critical resources is conducted entirely outside the traditional Western financial architecture.

As the race for the 21st-century’s essential commodities intensifies, the Belt and Road Initiative has proven to be a highly adaptable instrument of Chinese statecraft. It has evolved from a tool for exporting industrial overcapacity into a sophisticated mechanism for resource security. For the global community, the implications are profound. The transition to a green economy is now inextricably linked to Chinese capital and logistics. While the West attempts to build "friend-shoring" networks, Beijing’s deep-rooted financial and physical presence in the world’s most resource-rich regions suggests that any path to a renewable future will likely run through the infrastructure of the Silk Road.

In conclusion, the strategic pivot of the BRI signifies a move toward a more disciplined, resource-heavy investment portfolio. By pouring cash into the financing of global resources, Beijing is not just building roads; it is constructing a global architecture of dependency. The success of this strategy will depend on China’s ability to manage its own economic transition at home while navigating the increasingly complex political waters of its partners abroad. For now, the "resource grab" remains the centerpiece of China’s vision for a new global economic order, ensuring that when the world plugs in its future, the components are likely to have been financed, mined, and processed through the Belt and Road.