The emergence of the proposed "Board of Peace" within the framework of a second Trump administration represents more than a mere bureaucratic reshuffling; it signals a fundamental challenge to the post-1945 international order and the primacy of the United Nations. Designed as a high-level, lean, and results-oriented body, the Board of Peace is poised to bypass the traditional, often sclerotic, pathways of multilateral diplomacy in favor of a transactional, "America First" approach to global stability. By centralizing conflict resolution within the executive branch and leveraging the United States’ unmatched economic and military weight, this new entity threatens to marginalize the UN Security Council and redefine the very nature of international peacemaking.

At the heart of this shift is a profound philosophical divergence. For eight decades, the United Nations has operated on the principle of collective security and multilateral consensus, a system where nearly 200 nations ostensibly have a voice, even if the five permanent members of the Security Council hold the ultimate veto. The Board of Peace, by contrast, operates on the logic of the private sector—viewing international conflicts not as moral crises to be managed through endless committee meetings, but as disputes to be settled through high-stakes negotiation, leverage, and incentives. This "deal-making" architecture aims to replace the slow-moving machinery of UN General Assembly resolutions with bilateral breakthroughs that prioritize American strategic interests and regional stability over abstract notions of international law.

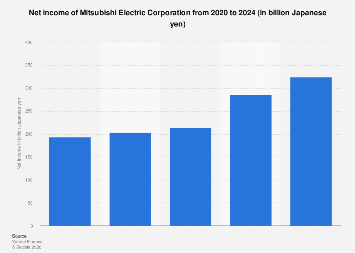

The potential for rivalry between the Board of Peace and the United Nations is rooted in the "power of the purse." The United States remains the largest financial contributor to the UN, providing roughly 22 percent of its core budget and 25 percent of its peacekeeping costs. In recent fiscal years, this has amounted to billions of dollars annually. If the Board of Peace becomes the primary vehicle for American diplomatic outreach, there is a significant likelihood that Washington will seek to divert funds from UN agencies toward this new unilateral body. Such a move would not only cripple the UN’s operational capacity in humanitarian and peacekeeping missions but would also force other global powers—specifically the European Union, China, and Japan—to decide whether they will fill the funding gap or follow the U.S. toward a more fragmented diplomatic landscape.

The blueprint for the Board of Peace can be found in the Abraham Accords, the landmark series of normalization agreements between Israel and several Arab nations. These deals were largely brokered outside the traditional UN framework and relied heavily on U.S.-led incentives, including arms sales, investment promises, and diplomatic recognitions. Supporters of this model argue that it achieved in months what the UN had failed to accomplish in decades: a tangible shift in regional dynamics. However, critics point out that such transactional diplomacy often ignores long-standing human rights concerns and international norms, creating a "pay-to-play" atmosphere that could embolden authoritarian regimes.

From an economic perspective, the Board of Peace could introduce a new era of "geopolitical arbitrage." By linking trade concessions, tariff exemptions, and direct foreign investment to peace agreements, the U.S. could effectively use its $27 trillion economy as a tool of pacification. This approach turns diplomacy into a market-driven exercise. For instance, in a hypothetical mediation between warring factions in Eastern Europe or Sub-Saharan Africa, the Board might offer reconstruction contracts and market access in exchange for immediate ceasefires. While this could lead to faster cessations of hostilities, it risks creating fragile "peace deals" that lack the institutional depth and local legitimacy that UN-led processes, despite their flaws, attempt to cultivate through civil society engagement and long-term development programs.

The rivalry with the UN is also likely to manifest in the realm of peacekeeping. Currently, the UN oversees more than a dozen peacekeeping operations globally, involving nearly 70,000 personnel. These missions are often criticized for their inefficiency and limited mandates. A Board of Peace could theoretically propose "private-public partnerships" for security or rely on regional coalitions funded directly by Washington, bypassing the need for Blue Helmet deployments. This would represent a significant shift in the global security architecture, moving away from a model of international neutrality toward one of explicit alignment with U.S. security objectives.

Market analysts and global risk consultants are already beginning to weigh the implications of this shift. The traditional "liberal international order" provided a predictable, albeit imperfect, set of rules for global trade and investment. A move toward a more transactional, board-led diplomacy introduces a higher degree of volatility. While a successful "deal" can open up new markets almost overnight—as seen with the surge in trade between Israel and the UAE post-2020—the lack of a permanent institutional framework means these deals are often tied to the specific political fortunes of the leaders who signed them. This "personalization of diplomacy" creates a unique set of risks for multinational corporations that rely on long-term stability.

Furthermore, the Board of Peace’s mandate would likely bring it into direct competition with the UN’s role in managing the world’s most intractable conflicts, most notably the war in Ukraine. While the UN has been largely sidelined by the Russian veto in the Security Council, it remains the primary venue for humanitarian aid and the "Black Sea Grain Initiative." A U.S.-led Board of Peace would likely seek a direct, bilateral settlement between Moscow and Kyiv, potentially offering a "grand bargain" that involves territorial concessions in exchange for security guarantees and the lifting of sanctions. Such a move would be a direct affront to the UN’s founding principle of the "territorial integrity of sovereign states," potentially rendering the UN Charter obsolete in the eyes of many global observers.

The rise of the Board of Peace also reflects a broader global trend toward "minilateralism"—the formation of small, functional groups of countries to address specific issues, rather than relying on massive, all-encompassing institutions. We see this in the expansion of the BRICS bloc, the strengthening of the Quad in the Indo-Pacific, and the growth of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The U.S. Board of Peace would be the ultimate expression of this trend, representing a "super-minilateralism" where the world’s leading superpower acts as the central hub for a network of bilateral spokes.

However, the challenges facing such a body are formidable. Diplomacy is not merely about closing a deal; it is about the painstaking work of implementation, monitoring, and verification. The United Nations, for all its bureaucratic bloat, possesses an institutional memory and a specialized workforce that a new, politically appointed board would struggle to replicate. Issues such as refugee repatriation, landmine clearance, and transitional justice require decades of sustained effort—work that does not always provide the immediate, "headline-grabbing" results that a politically driven board might crave.

As the global community watches the potential stand-up of this new entity, the tension between the "old guard" of the UN and the "new guard" of the Board of Peace will likely define the next decade of international relations. If the Board succeeds in brokering major peace deals, it could provide a much-needed jolt to a global diplomatic system that many feel has become ineffective. Conversely, if it undermines the UN without providing a stable alternative, it could lead to a "G-Zero" world—a state of global leadership vacuum where no single country or institution has the authority or the will to maintain order.

Ultimately, the Board of Peace represents a bet that the 21st century will be defined by sovereign interests rather than global governance. By treating peace as a commodity to be negotiated rather than a collective right to be protected, the Board seeks to leverage American exceptionalism in its most raw, commercial form. Whether this leads to a more stable world or a more chaotic one depends on whether the art of the deal can truly replace the science of diplomacy. As the rivalry with the United Nations intensifies, the world may find itself at a crossroads between the enduring ideals of the mid-20th century and a new, more ruthless era of geopolitical competition.