The Islamic Republic of Iran has once again deployed its most potent domestic weapon in the face of escalating civil unrest: the digital kill switch. As protests ripple through major urban centers, the Tehran administration has implemented a near-total internet blackout, effectively severing the country’s 85 million citizens from the global community. While the immediate objective is the disruption of protest logistics and the suppression of real-time documentation of state crackdowns, the long-term economic and structural ramifications of such digital isolationism are profound. This systemic dismantling of connectivity represents not merely a temporary security measure, but a decisive pivot toward a "splinternet" model that threatens to paralyze Iran’s already fragile private sector.

The mechanics of the current blackout involve a sophisticated combination of mobile network disruptions, the throttling of fixed-line broadband, and the targeted blocking of encrypted messaging platforms. According to data from network monitors, traffic levels in Iran have plummeted to less than 20% of their normal capacity during peak periods of unrest. This is not a blunt disconnection but a calculated filtration. By utilizing the National Information Network (NIN)—a domestic intranet colloquially known as the "Halal Internet"—the state maintains essential services like banking and government administration while denying citizens access to external platforms such as Instagram, WhatsApp, and Twitter. This dual-track system allows the regime to keep the machinery of the state humming while the social and commercial lives of its people are plunged into darkness.

The economic cost of these disruptions is staggering. Estimates from international digital rights groups and economic analysts suggest that a total internet shutdown costs the Iranian economy approximately $37 million per day in lost productivity and trade. However, the indirect costs are arguably higher. Over the past decade, Iran has fostered a burgeoning tech ecosystem, with domestic startups attempting to replicate the success of Western giants like Amazon and Uber. These firms, ranging from the ride-hailing app Snapp to the e-commerce giant Digikala, rely on stable connectivity to manage logistics, process payments, and communicate with millions of users. When the internet goes dark, the digital economy—one of the few sectors that had shown resilience under the weight of international sanctions—grinds to a halt.

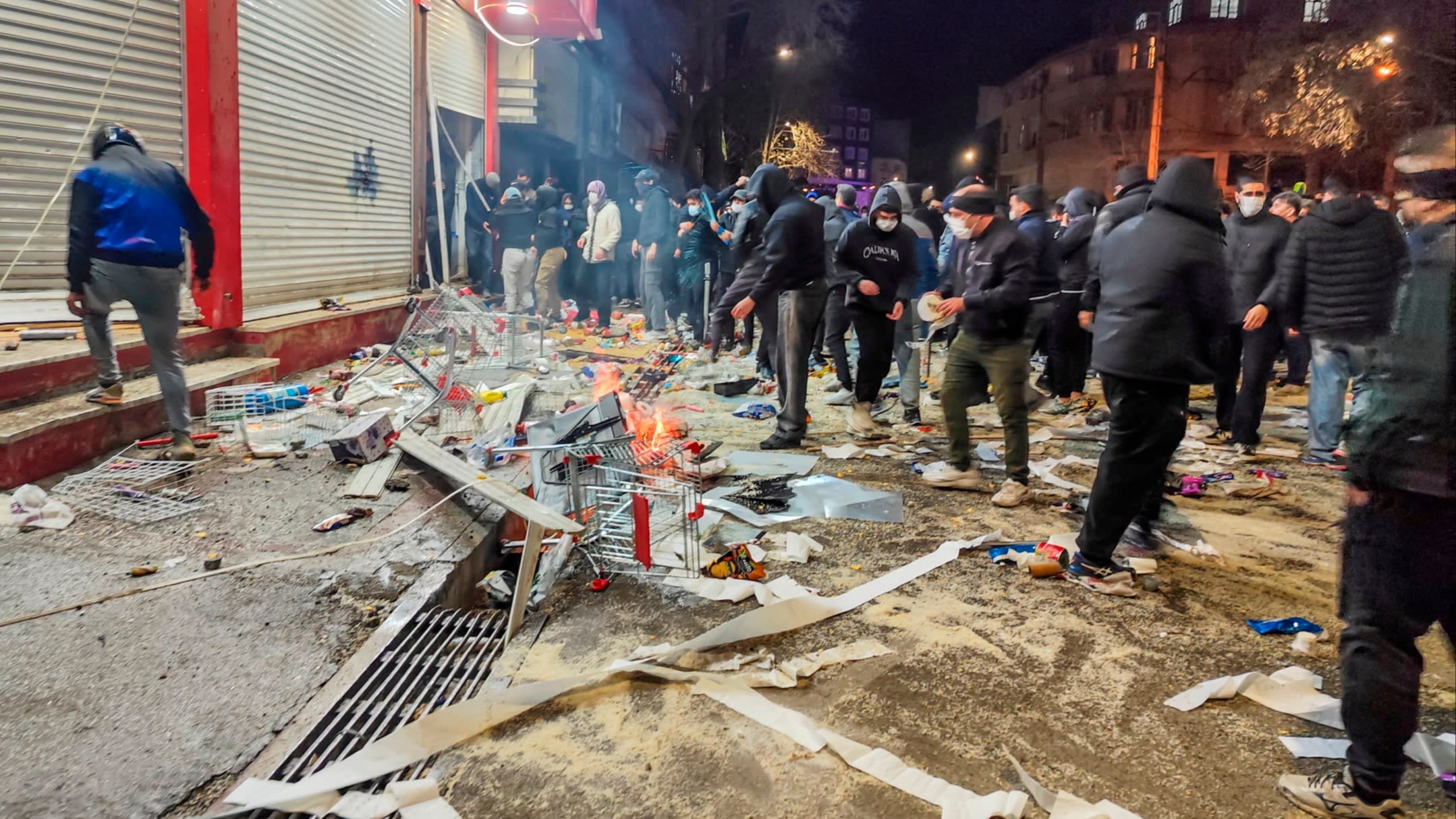

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are particularly vulnerable. In Iran, Instagram has evolved into a vital marketplace for hundreds of thousands of micro-businesses, many of which are run by women in rural areas selling artisanal goods, clothing, and food. Without access to these platforms, these entrepreneurs lose their primary source of income overnight. Analysts estimate that as many as one million jobs are directly or indirectly tied to the social media economy in Iran. By severing these links, the government is not just silencing political dissent; it is dismantling the livelihoods of a demographic already suffering from runaway inflation and a depreciating currency.

The strategy of digital isolation also exacerbates the "brain drain" that has plagued Iran for decades. The country boasts one of the most highly educated populations in the Middle East, with a surplus of skilled software engineers and data scientists. Yet, the persistent threat of connectivity loss and the increasing censorship of the web have made Iran an untenable environment for tech talent. Many of Iran’s brightest minds are migrating to hubs like Dubai, Istanbul, or Berlin, seeking the digital stability required for a modern career. This exodus of human capital represents a generational loss for the Iranian economy, ensuring that even if political stability returns, the foundations for a modern, high-tech recovery have been severely eroded.

From a global perspective, Iran’s approach to digital sovereignty is part of a broader, more alarming trend toward "technological authoritarianism." While countries like India lead the world in the sheer number of localized internet shutdowns, Iran’s model is more akin to China’s "Great Firewall," albeit with more volatile implementation. Unlike China, which has successfully built a self-contained digital universe over decades, Iran’s attempts to migrate its populace to domestic platforms have met with significant resistance. Citizens view state-sanctioned apps with deep suspicion, fearing they are tools for surveillance and data harvesting. Consequently, the "cat-and-mouse" game between censors and the public continues, with millions of Iranians turning to Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and proxy servers to bypass restrictions.

The geopolitical implications of the blackout are equally significant. For Western policymakers, the internet shutdown presents a complex challenge: how to support the Iranian people’s right to information without violating existing sanctions or providing the regime with more advanced surveillance tools. The U.S. Treasury Department has recently updated its General License D-2 to allow American tech companies to provide more services to Iranians, including cloud computing and privacy tools. Furthermore, the deployment of satellite-based internet services, such as SpaceX’s Starlink, has been touted as a potential solution to bypass the state-controlled infrastructure. However, the logistical hurdle of smuggling hardware terminals into the country remains a formidable barrier to widespread adoption.

The Iranian government’s reliance on the National Information Network also signals a shift in its economic philosophy. By attempting to decouple from the global web, Tehran is signaling a preference for a "resistance economy"—a self-sufficient model designed to withstand external pressures and internal dissent. Yet, this isolationism is a double-edged sword. Modern global trade is intrinsically linked to the flow of data. By restricting this flow, Iran is effectively placing a ceiling on its own economic potential. Foreign investors, already wary of the legal and political risks of entering the Iranian market, are further deterred by an environment where the fundamental infrastructure of business can be switched off at a moment’s notice.

The psychological impact of these blackouts on the Iranian populace cannot be overstated. In an era where digital connectivity is increasingly viewed as a fundamental human right, the sudden loss of access to the world creates a profound sense of claustrophobia and abandonment. For the youth of Iran—who make up more than 60% of the population—the internet is not just a luxury; it is their window to the world, their school, and their social circle. The regime’s attempt to shutter this window is a testament to its fear of the mobilizing power of information, but it also highlights the widening chasm between the ruling elite and a tech-savvy generation that views digital freedom as non-negotiable.

Looking ahead, the trajectory of Iran’s digital policy suggests a future of increased fragmentation. The state is likely to continue investing in the NIN, refining its ability to perform "surgical" shutdowns that target specific regions or demographics while sparing the industrial and financial sectors. This "targeted" approach aims to minimize economic damage while maximizing political control. However, as the protests have shown, the demand for connectivity is resilient. Each shutdown drives a new wave of innovation in circumvention technology, creating a cycle of escalation that shows no sign of abating.

In conclusion, the internet blackouts in Iran are more than a temporary disruption; they are a manifestation of a fundamental conflict between state control and the modern global economy. The economic price of these actions—measured in billions of dollars of lost GDP, a crippled tech sector, and an accelerating brain drain—is a cost the regime seems willing to pay to ensure its survival. However, as the digital iron curtain descends, the long-term viability of an economy severed from the global information flow remains highly doubtful. For Iran, the choice is increasingly stark: embrace the digital integration required for 21st-century prosperity, or risk total obsolescence in a world that is moving forward without it.