As the melting ice of the High North reveals a treasure trove of untapped resources and opens new maritime corridors, the geopolitical status of Greenland has shifted from a peripheral concern to a central pillar of North American and European security. Recent commentary from Scott Bessent, a prominent figure in global finance and a key economic advisor in U.S. political circles, has reignited a contentious debate regarding the ability of European powers to safeguard the world’s largest island. Bessent’s assertion that Europe remains fundamentally "too weak" to guarantee Greenland’s security reflects a burgeoning school of thought in Washington that views the Arctic not merely as a climate-change laboratory, but as a critical theater of competition where traditional alliances are being tested by economic and military realities.

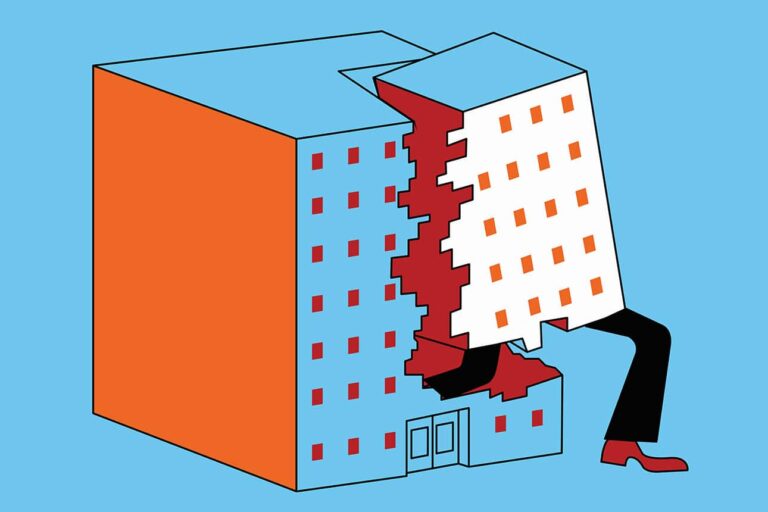

The core of this argument rests on the widening gap between Europe’s stated defense ambitions and its actual fiscal and logistical capacity. While the Kingdom of Denmark maintains formal sovereignty over Greenland, the vastness of the territory—stretching over 2.1 million square kilometers—presents a surveillance and defense challenge that far outstrips the capabilities of the Danish Defense Force or the collective security mechanisms of the European Union. For decades, the security of Greenland has been a quiet partnership, underpinned by the 1951 defense treaty between the U.S. and Denmark, which allows for a permanent American military presence at Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule Air Base). However, critics like Bessent argue that as Russia militarizes its Arctic coastline and China declares itself a "near-Arctic state," the status quo of relying on a fragmented European defense architecture is no longer viable.

From an economic perspective, the urgency is driven by the global race for critical minerals. Greenland is home to some of the world’s most significant deposits of rare earth elements (REEs), including neodymium, praseodymium, and dysprosium—materials essential for the production of electric vehicle motors, wind turbines, and advanced military hardware. Currently, China controls approximately 60% of global REE production and nearly 90% of refining capacity. For the United States and its allies, securing access to Greenland’s mineral wealth is not just a matter of trade; it is a prerequisite for the "green transition" and technological independence. The Kvanefjeld project in southern Greenland, despite local political sensitivities regarding uranium mining, highlights the immense stakes involved. Financial analysts suggest that the development of Greenland’s mining sector could transform the island’s economy, potentially paving the way for full independence from Copenhagen—a prospect that would create a massive security vacuum if not managed under a robust Western umbrella.

The skepticism toward European security guarantees is further fueled by the continent’s ongoing struggle to meet NATO defense spending targets. While the conflict in Ukraine has spurred a rearmament phase across Europe, the primary focus remains on the eastern flank. The High North, by contrast, requires specialized capabilities: icebreakers, long-range maritime patrol aircraft, and satellite-based surveillance systems capable of operating in extreme environments. Russia currently maintains a fleet of over 40 icebreakers, including nuclear-powered vessels that can operate year-round. In comparison, the U.S. Coast Guard is only beginning to revitalize its aging fleet, and European nations, with the exception of Norway and perhaps Finland, possess limited capacity to project power into the deep Arctic. This "icebreaker gap" is a physical manifestation of the weakness Bessent alludes to—a deficit of hardware that makes European promises of security seem aspirational rather than credible.

Furthermore, the economic fragility of the Eurozone complicates the security picture. With aging populations and significant sovereign debt burdens, many European nations face a "guns vs. butter" dilemma that restricts their ability to invest in the multi-decade infrastructure projects required to secure the Arctic. Washington’s perspective, increasingly influenced by "America First" realism, suggests that if the U.S. is the only power capable of providing the necessary security infrastructure, it should have a more direct hand in the island’s strategic orientation. This is not a new sentiment—the 2019 suggestion by the Trump administration to "purchase" Greenland was met with international derision, yet the underlying logic of integrating Greenland into the North American defense and economic perimeter remains a persistent theme in U.S. strategic circles.

China’s "Polar Silk Road" initiative represents the other side of the strategic coin. Beijing has attempted to gain a foothold in Greenland through infrastructure investments, including proposed airport expansions and mining ventures. While the Danish government, under pressure from Washington, has largely blocked these overtures, the economic pressure on Greenland’s Home Rule government remains high. Greenland relies on an annual block grant from Denmark of approximately $600 million, which accounts for more than half of its public budget. If Greenland seeks to diversify its economy and move toward autonomy, the temptation to accept Chinese capital will inevitably grow. Bessent’s critique suggests that Europe lacks the financial "firepower" to offer Greenland a viable economic alternative to Chinese investment, leaving the U.S. as the only actor capable of acting as both a security guarantor and a primary investment partner.

The strategic importance of the GIUK gap—the naval transit point between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom—cannot be overstated. During the Cold War, this was the frontline of anti-submarine warfare. Today, it is the gateway through which Russian Northern Fleet vessels must pass to reach the Atlantic. If Greenland’s security is perceived as "weak" or porous, it compromises the entire northern defense of the United States and Canada. The North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) is currently undergoing a multi-billion-dollar modernization program, and Greenland is a vital node in this network. The argument for a more assertive U.S. role is predicated on the idea that the defense of the American homeland is inextricably linked to the stability and security of the Greenlandic landmass.

However, any shift in the security paradigm must navigate the complexities of Greenlandic domestic politics. The Inuit people, who make up the vast majority of the population, have a deep-seated desire for self-determination. They view their land not as a strategic asset for superpowers, but as a homeland facing the existential threat of climate change. Any U.S.-led security framework that ignores the social and economic needs of the local population is likely to face resistance. For a "weak" Europe to be replaced by a "strong" America, the partnership must move beyond military bases and into the realm of sustainable development, education, and healthcare infrastructure.

In the corridors of power in Brussels and Copenhagen, Bessent’s comments are likely viewed as a provocation or a sign of renewed American isolationism. Yet, the data suggests a shift in the center of gravity. U.S. diplomatic presence in Greenland has increased significantly, with the reopening of a consulate in Nuuk in 2020 and the announcement of various economic aid packages. These moves indicate that regardless of the rhetoric, the U.S. is already moving to fill the perceived security gap left by Europe.

As the Arctic continues to warm at nearly four times the global average, the "High North, Low Tension" policy that has defined the region for decades is rapidly eroding. The competition for the Arctic is a marathon, not a sprint, and it requires a level of sustained investment and strategic clarity that many in Washington fear Europe is currently unable to provide. Whether Greenland remains a semi-autonomous part of the Kingdom of Denmark or moves toward a more explicit alignment with North American security structures will be one of the defining geopolitical questions of the mid-21st century. The assertion that Europe is "too weak" to hold the line is a blunt assessment, but in the unsentimental world of realpolitik, it is a warning that the Arctic’s future may be decided by those with the deepest pockets and the most icebreakers. For now, the eyes of the world remain fixed on the northern horizon, where the shifting ice serves as a precursor to a shifting global order.