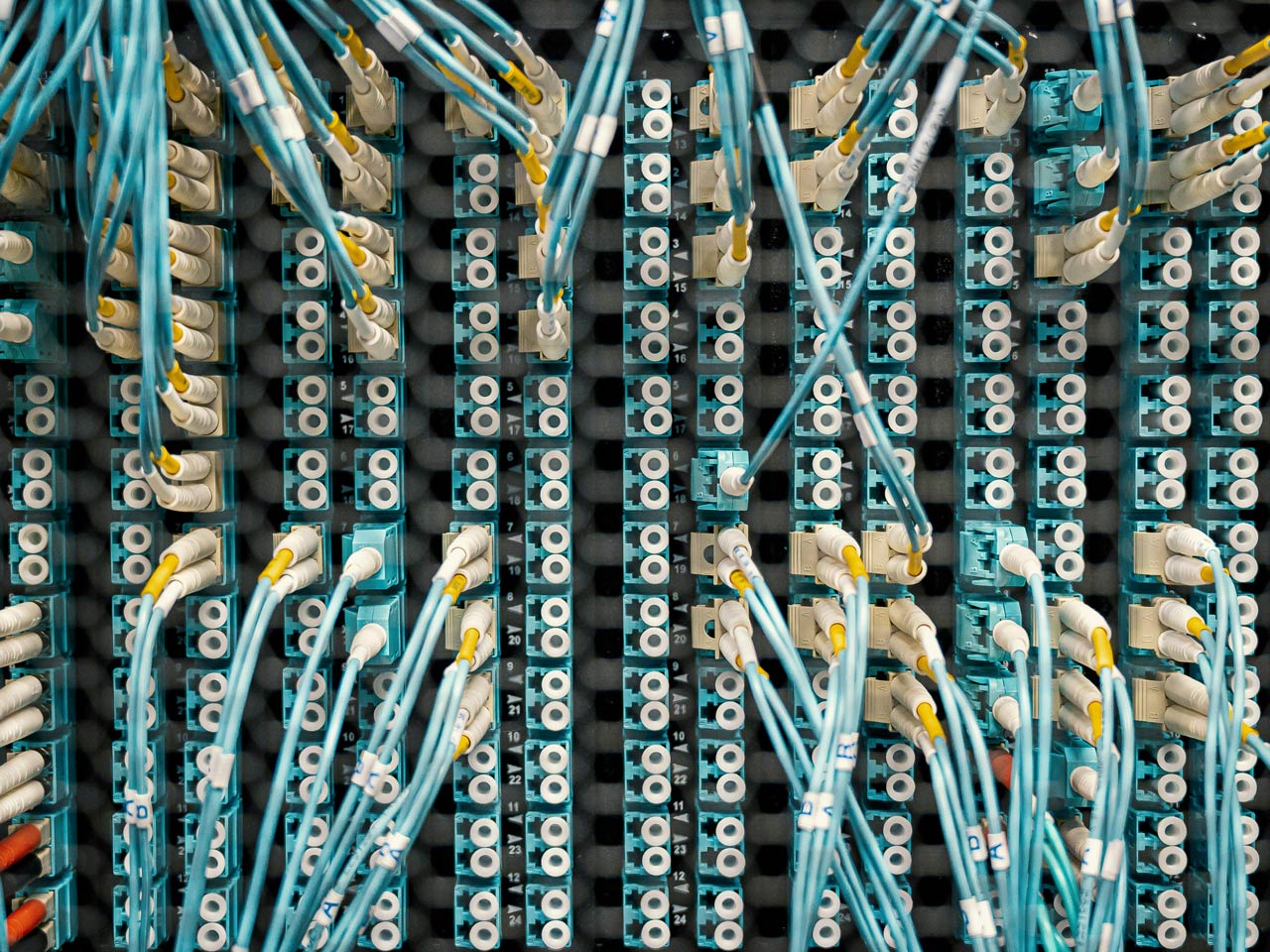

Global financial institutions and consulting firms are projecting a staggering $5 trillion to $7 trillion in capital expenditure for data center build-outs worldwide between 2026 and 2030, translating to an average annual investment of $1 trillion. This colossal sum underscores the unprecedented demand for computing power, driven primarily by the artificial intelligence revolution. To contextualize this scale, Bank of America estimates that constructing one gigawatt (GW) of data center capacity costs approximately $50 billion. At this rate, an annual investment of $1 trillion would facilitate the development of roughly 20 GW of new capacity, a volume three times greater than New York’s current installed electricity capacity of approximately 6.7 GW.

The urgency to meet this demand is palpable. Silicon Valley has witnessed a flurry of intricate circular financing arrangements in 2025, where major technology conglomerates and burgeoning AI startups are increasingly investing in each other, blurring the traditional lines between customer, supplier, and investor. Notable examples include OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank’s commitment of $500 billion for their "Stargate" project over the next four years, and CoreWeave’s $14 billion agreement with Meta to provide computing power. Goldman Sachs anticipates that capital expenditures for AI hyperscalers alone could reach $394 million by the end of 2025.

However, the critical challenge lies in the financing mechanisms for this exponential growth. While hyperscalers like Meta, with their substantial balance sheets, can absorb such commitments, the path for standalone AI developers is far less clear. OpenAI, despite generating an estimated $20 billion in annual recurring revenue (ARR) in 2025, has publicly stated an intention to invest $1.4 trillion over the next eight years, a figure that dwarfs its current revenue streams.

Examining past funding strategies offers insight into potential future pathways. Initially, hyperscalers financed early AI investments through their own robust cash flows. In 2025 alone, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet collectively commanded approximately $500 billion in free cash flow. As the transformative potential of AI became more apparent, the debt capital market emerged as a significant funding source. However, with leverage ratio constraints, these entities have begun to explore off-balance-sheet financing solutions. A prime illustration of this trend is Meta’s Hyperion Data Center project in Louisiana. In October 2025, Meta established a joint venture with Blue Owl Capital, creating a special-purpose vehicle (SPV) named Beignet Investor. This SPV successfully raised $30 billion, comprising $27 billion in loans from private credit funds and $3 billion in equity from Blue Owl.

Looking forward, Morgan Stanley’s July 2025 report projected data center capital expenditures to reach approximately $3 trillion by 2028. The bank estimated that hyperscalers could cover half of this amount through their internal cash flows, with an additional $200 billion potentially financed through corporate debt issuance. Crucially, the report highlighted that approximately $150 billion could be sourced through data center asset-backed securities (ABS) and commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), signaling a growing interest in securitization as a funding tool.

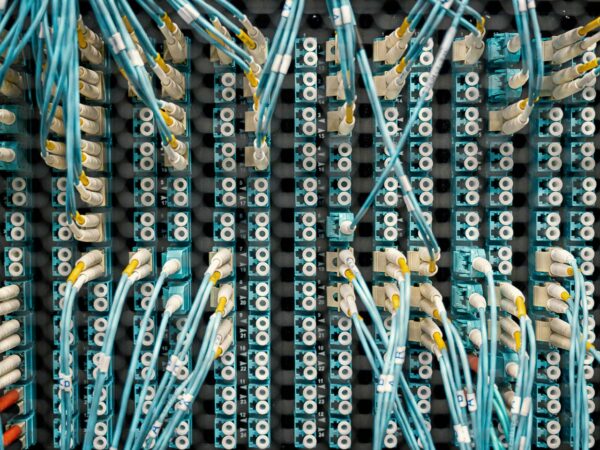

Data centers have not been entirely absent from the securitization market, though their utilization of structured finance instruments has been relatively limited. The inaugural global data center ABS was issued in February 2018 by Vantage Data Centers, a prominent operator in key US markets. This securitization, rated A- by Standard & Poor’s, raised $1.125 billion, enabling Vantage to expand its operations. Three years later, in 2021, Blackstone issued the first-ever data center CMBS, securing $3.2 billion to support its $10 billion acquisition of QTS Realty Trust.

In Europe, the data center securitization landscape is still nascent, with only a handful of deals to date. In June 2024, Vantage issued £600 million in securitized term notes backed by two data centers in Wales, marking the first European data center ABS. A year later, in June 2025, Vantage raised an additional €640 million in securitized term notes for four data centers in Frankfurt and Berlin, Germany, establishing the first continental European data center ABS. Globally, 2025 saw the issuance of 27 data center ABS deals, collectively raising $13.3 billion, a 55% year-over-year increase, according to the New York Times.

The structural characteristics of data centers lend themselves to securitization. Current data center securitization transactions are typically issued by operators who possess long-term contractual cash flows derived from lease agreements with co-location clients or hyperscalers. The proceeds from these issuances are generally allocated towards refinancing existing debt and expanding data center capacity.

Against this backdrop, the intricate web of circular financing arrangements observed in 2025 has propelled the rise of "neocloud" providers. These entities offer AI developers access to computing power on a rental basis through a GPU-as-a-Service (GPUaaS) model. This operational expenditure-focused approach shifts significant upfront capital expenditure for AI infrastructure to more flexible, pay-as-you-go costs for training and inference. Leading neocloud providers have recently secured substantial long-term contracts with hyperscalers. For instance, Amsterdam-based Nebius has an agreement with Microsoft to provide GPU services with a total contract value of up to $19.4 billion through 2031, and a separate $3 billion, five-year agreement with Meta. These long-dated contractual obligations generate predictable and stable cash flows, theoretically making computing power securitizable in a manner analogous to how data center operators issue ABS and CMBS.

While high-profile securitization transactions backed by computing power contracts have yet to materialize, reports suggest that some investment bankers are exploring such deals for AI debt. However, the details of these nascent transactions remain largely undisclosed.

The broader picture for AI infrastructure financing has become more complex in recent months, with early signs of strain emerging across the AI ecosystem. The equity capital markets have begun to re-evaluate the sustainability of AI-driven investments. Oracle’s stock, for example, experienced a significant decline of 43% from its peak in early September 2025 to December 23, 2025, following its $300 billion computing power deal with OpenAI, which spans five years. This market sentiment shift is also evident in derivatives markets, where Oracle’s five-year credit default swap (CDS) surged from approximately 37 basis points in July to 151.3 basis points in November 2025, reaching its highest level since 2009, as reported by Bloomberg.

The magnitude of this market reaction reflects widespread concerns about the feasibility of Oracle’s recent expansion strategy. In its latest 10-Q earnings report, Oracle disclosed $248 billion in additional lease commitments, largely tied to its AI infrastructure build-out. The primary concerns surrounding Oracle, as highlighted by Bloomberg, are twofold. Firstly, there appears to be a mismatch between the duration of Oracle’s lease commitments, which are expected to span 15 to 19 years, and the tenor of its contracted revenues, most of which are due within the next five years. This exposes the company to renewal risk and the potential for excess capacity if AI demand softens. Secondly, there is a risk that Oracle may under-depreciate its GPUs, necessitating server upgrades mid-lease. The company currently depreciates IT equipment over six years, aligning with industry norms. However, the long-term lifespan of GPUs remains an open question, particularly given that foundational models like ChatGPT have only been widely available for a short period. Similar market pressures have impacted other players, with CoreWeave and Nebius shares sliding 55% and 30% from their respective peaks by the end of 2025.

Despite these sharp equity corrections, the overall outlook for AI infrastructure funding remains robust. Sung Cho, co-head of public tech investing and US fundamental equity at Goldman Sachs, expressed confidence in the sustainability of AI funding in a December 2025 interview with CNBC. He noted that, in aggregate, 90% of the capital expenditure to date in AI has been financed by hyperscalers’ operating cash flows, with only 10% sourced from corporate debt. Significantly, the majority of this corporate debt has been issued by Meta, whose credit ratings surpass those of the U.S. government.

For computing power ABS and other more innovative financing vehicles to achieve widespread adoption, clearer evidence of AI monetization will be crucial. In the near term, the development of a viable business-to-business-to-consumer (B2B2C) model, where AI adoption directly translates into demonstrable productivity gains and margin expansion for end customers, could pave the way. Once these economic underpinnings are firmly established, computing power ABS deals may become a mainstream financing option, diversifying the spectrum of capital solutions available to the rapidly evolving AI industry.