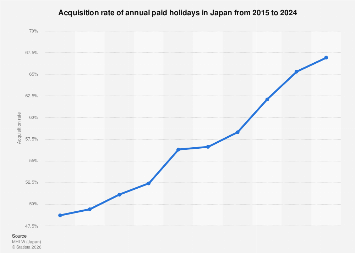

A recent analysis of Japanese labor trends for 2024 highlights a persistent challenge: the underutilization of accrued paid leave, a phenomenon that continues to draw attention from economists, policymakers, and international observers alike. While Japanese employees are legally entitled to a significant number of paid vacation days, the actual rate at which these days are taken remains notably low, raising questions about work-life balance, productivity, and the broader economic implications for one of the world’s largest economies.

The data indicates that while companies allocate a statutory minimum of paid holidays, often ranging from 10 days for new employees to 20 days for those with longer tenure, the proportion of these days actually consumed by workers falls considerably short. This disconnect is not a new development; it has been a characteristic of the Japanese work culture for decades, often attributed to a complex interplay of societal expectations, corporate pressures, and deeply ingrained notions of dedication to one’s employer.

Economic analysts point to several contributing factors. Foremost among these is the prevailing culture of "karoshi," or death from overwork, a stark reminder of the extreme dedication sometimes expected and voluntarily given by Japanese workers. While the government has made efforts to curb excessive working hours and promote a healthier work-life balance, the subtle, and sometimes not-so-subtle, pressures to remain available and dedicated to one’s job can discourage employees from taking extended periods of leave. The fear of falling behind on work, appearing less committed than colleagues, or burdening team members can outweigh the benefit of personal time off.

Furthermore, the structure of the Japanese economy, with its emphasis on long-term employment and company loyalty, can exacerbate this issue. Employees may feel a sense of obligation to their employers, particularly in industries where long-term projects and close-knit teams are the norm. This can create an environment where taking a full week or more of vacation might be perceived as disruptive or even detrimental to team cohesion and project timelines.

Statistics from various labor surveys consistently show that the average number of paid holidays taken per employee in Japan is significantly lower than the number accrued. While precise figures can fluctuate annually and vary by industry and company size, reports from organizations like the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare have, in the past, indicated that the utilization rate can be as low as 50% in some sectors. This means that for every two days of paid leave an employee is entitled to, they may only take one, effectively forfeiting valuable personal time.

This trend has broader economic ramifications. A workforce that is consistently overworked and under-rested is less likely to be as productive or innovative in the long run. Burnout can lead to decreased efficiency, increased errors, and higher rates of absenteeism due to stress-related illnesses. From a macroeconomic perspective, a population that is not taking adequate time for rest and rejuvenation may also have a reduced capacity for discretionary spending, impacting sectors reliant on consumer demand.

Comparatively, many Western economies, particularly in Europe, boast much higher rates of paid holiday utilization. Countries like France, Spain, and Germany, for instance, often have statutory minimums that are similar to or even exceed Japan’s, but their cultural norms and labor laws are more conducive to employees taking their full entitlement. This often translates into more robust tourism industries and a generally more balanced approach to work-life integration. The United States, while not having a federal mandate for paid vacation, sees higher utilization rates in companies that do offer it, reflecting a different cultural emphasis on leisure and personal time.

In Japan, the government has been implementing policies aimed at addressing this issue. These include promoting "time-off management" initiatives, encouraging companies to track and manage employee leave, and raising awareness about the importance of work-life balance. Some companies are experimenting with innovative approaches, such as mandatory leave days or encouraging shorter, more frequent breaks, in an effort to nudge employees towards taking their earned time off. However, overcoming deeply ingrained cultural norms and corporate practices is a slow and arduous process.

The economic impact of low holiday utilization extends beyond individual employee well-being and productivity. It can influence the national consumption patterns and contribute to a perception of a less dynamic and engaged workforce. A workforce that is constantly on the brink of exhaustion may be less likely to contribute to the kind of creative problem-solving and entrepreneurial ventures that drive economic growth. Furthermore, the healthcare costs associated with stress-related illnesses and burnout can place an additional burden on the social security system.

Market data from employment agencies and human resources consultancies in Japan often reveal that companies are increasingly looking to improve employee well-being as a means to attract and retain talent. Offering more attractive leave policies, and crucially, fostering a culture that encourages their use, is becoming a competitive advantage. However, this requires a fundamental shift in managerial attitudes and employee expectations.

The challenge for Japan is to strike a delicate balance: maintaining its reputation for diligence and commitment while ensuring that its workforce is not sacrificing its health and personal well-being on the altar of professional dedication. The continued low rate of paid holiday utilization in 2024 serves as a potent reminder that while legal entitlements exist, the real measure of progress lies in the cultural adoption and practical implementation of a sustainable work-life balance. The economic and social dividends of a well-rested and rejuvenated workforce are too significant to ignore, and addressing this persistent issue remains a critical priority for Japan’s long-term prosperity and the health of its citizens.