The Arctic, once a peripheral theater of global affairs, has rapidly transformed into a focal point of 21st-century geopolitical and economic competition. At the center of this shifting landscape is Greenland, an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark, which has become the unlikely catalyst for a significant rift in the Transatlantic alliance. The resurgence of interest in acquiring the world’s largest island has moved beyond mere diplomatic curiosity, evolving into a hardline economic negotiation characterized by the threat of punitive trade measures. By leveraging the power of tariffs against long-standing allies, the United States is signaling a fundamental shift toward a transactional foreign policy where territorial strategy and trade access are inextricably linked.

The strategic rationale for Greenland’s integration into the American sphere of influence is rooted in both defense and resource security. As polar ice melts at an unprecedented rate, the High North is witnessing the opening of new shipping lanes—the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage—which could drastically reduce transit times between Asia, Europe, and North America. Simultaneously, Greenland sits atop massive, untapped deposits of critical minerals and rare earth elements (REEs), including neodymium, praseodymium, dysprosium, and terbium. These materials are essential for the production of everything from electric vehicle batteries to advanced missile guidance systems. Currently, China controls approximately 85% to 90% of the global processing capacity for these minerals, making Greenland’s potential reserves a matter of national security for Washington.

However, the proposal to purchase Greenland has met with a resolute "not for sale" from the Danish government in Copenhagen and the Greenlandic parliament in Nuuk. This rejection has prompted a move toward coercive economic diplomacy, with the threat of tariffs serving as a primary lever of pressure. For the United States, the use of Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962—which allows for tariffs based on national security grounds—has become a preferred tool to bypass traditional diplomatic channels. By framing the Greenland acquisition as a necessity for Arctic security, the administration positions any opposition as a hurdle to Western defense, thereby justifying economic penalties.

The economic implications of such a move would be far-reaching, potentially destabilizing a trade relationship between the US and the European Union that exceeds $1.3 trillion annually. Denmark, though a small economy relative to the US, is a critical player in several high-value sectors. Danish exports to the US include pharmaceuticals, machinery, and renewable energy technology, specifically wind turbine components produced by industry leaders like Vestas. A targeted tariff regime would not only raise costs for American consumers and manufacturers but would also likely trigger retaliatory measures from the European Commission, which handles trade policy for all EU member states.

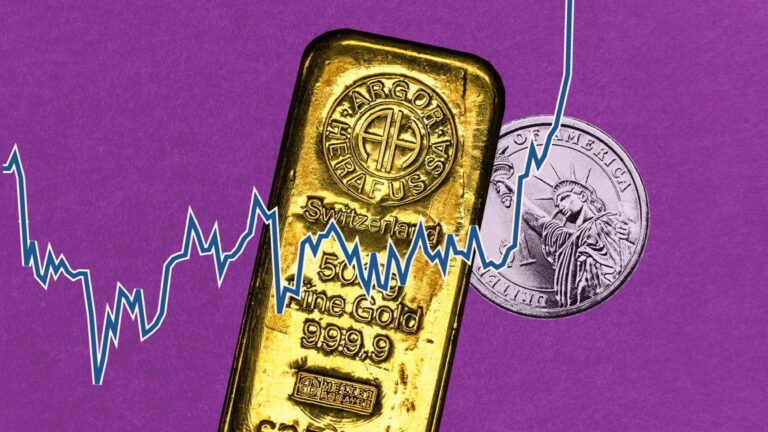

The prospect of a trade war over Arctic territory introduces a new layer of volatility to global markets. Investors in the mining and energy sectors are particularly sensitive to these developments. While Greenland’s mineral wealth is vast, the cost of extraction in an environment with minimal infrastructure is prohibitive. Stability and long-term cooperation are prerequisites for the billions of dollars in capital investment required to bring these resources to market. If the region becomes a theater of trade disputes and diplomatic hostility, the risk premium for Arctic projects will skyrocket, potentially delaying the very resource diversification the US seeks to achieve.

Furthermore, the threat of tariffs highlights a widening ideological gap within NATO. For decades, the alliance has been built on the premise of shared security interests and the promotion of liberalized trade. The introduction of territorial demands backed by economic threats challenges the sovereign integrity of member states. From the perspective of Copenhagen, Greenland is not a commodity to be traded but a constituent part of the Kingdom with its own burgeoning movement toward independence. The Danish government currently provides a "block grant" of approximately $600 million annually to Greenland, accounting for more than half of the island’s public budget. Any US attempt to force a sale through economic coercion is viewed in Europe as an affront to the rules-based international order.

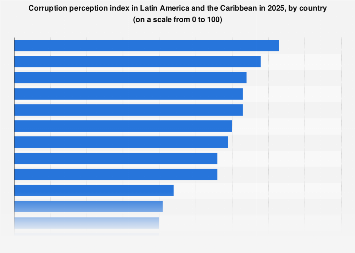

In the broader context of global competition, the friction between the US and its allies over Greenland provides an opening for rival powers. Russia has been aggressively militarizing its Arctic coastline, reopening Cold War-era bases and deploying advanced S-400 missile systems. China, meanwhile, has declared itself a "Near-Arctic State" and is actively pursuing its "Polar Silk Road" initiative. Beijing has already attempted to invest in Greenlandic infrastructure, including airports and mining projects, though these efforts were largely blocked by Danish and American intervention. If the US alienates its European partners through aggressive trade tactics, it may inadvertently weaken the unified front necessary to check Sino-Russian ambitions in the High North.

The economic impact on Greenland itself must also be scrutinized. The island’s economy is currently heavily dependent on fishing, which accounts for over 90% of its exports. While the US represents a growing market for Greenlandic cold-water shrimp and halibut, the local government is eager to diversify through tourism and mining. However, Nuuk is also cautious about becoming a pawn in a superpower struggle. Local leaders have expressed a desire for American investment, but they emphasize that such investment must come on Greenlandic terms, focusing on sustainable development and local employment rather than a total transfer of sovereignty.

From a macroeconomic perspective, the use of tariffs as a diplomatic cudgel reflects a broader trend toward "mercantilist" diplomacy. This approach treats trade deficits and market access as zero-sum games. If the US follows through with tariffs against Denmark or the EU over the Greenland issue, it would likely target specific sectors to maximize political pain. For instance, a 25% tariff on Danish medical products or specialized machinery would hit the Danish economy where it is most vulnerable. Yet, such a move would also disrupt the supply chains of American pharmaceutical giants and manufacturers who rely on Danish precision engineering.

The legal and institutional hurdles to such a policy are significant. The World Trade Organization (WTO) has historically been the arbient of trade disputes, but its appellate body has been effectively neutralized in recent years, leaving little recourse for smaller nations facing unilateral tariffs from larger economies. This "might makes right" environment creates a chilling effect on international cooperation, as nations begin to prioritize self-sufficiency and protectionism over the efficiencies of global trade.

As the ice continues to recede, the geopolitical temperature in the Arctic is set to rise. The Greenland controversy is a harbinger of a future where strategic geography and economic policy are indistinguishable. Whether the US can achieve its Arctic objectives through traditional partnership or whether it will continue to lean on the threat of trade barriers remains the central question for the Transatlantic alliance. The outcome will not only determine the future of Greenland but will also redefine the limits of economic leverage in modern statecraft.

In conclusion, the intersection of territorial ambition and trade policy represents a high-stakes gamble. While the allure of Greenland’s resources and its strategic position is undeniable, the cost of pursuing these goals through economic warfare against allies may outweigh the benefits. A fractured West, divided by tariffs and diplomatic resentment, is ill-equipped to manage the complex challenges of a rapidly changing Arctic. For the global economy, the shift toward using trade as a weapon of territorial acquisition introduces a new era of uncertainty, where the boundaries between commercial interests and national security are permanently blurred. Moving forward, the international community will be watching closely to see if the Arctic remains a zone of "high tension, low conflict," or if it becomes the next major flashpoint in a world defined by economic nationalism.