Gold prices are experiencing an unprecedented surge, recently hitting a new record high of $4,000 per troy ounce in the second week of October 2025. This remarkable ascent, which has seen gold prices effectively double in less than two years, is largely attributed to a significant uptick in central bank stockpiling of bullion and robust investor inflows into gold-backed funds. While there was a noticeable, albeit brief, deceleration in central bank acquisitions during July 2025, the overarching trend points towards a sustained and strategic re-engagement with the precious metal.

This renewed fascination with gold by monetary authorities appears to be a direct consequence of escalating geopolitical risks and a growing apprehension regarding the long-term stability of the US dollar as the primary global reserve currency. Analysts suggest that a significant portion of this shift involves central banks deliberately diversifying away from dollar-denominated assets. Compounding these concerns, the global bond markets have endured a period of considerable volatility throughout the year, further diminishing the appeal of traditional fixed-income instruments. In a notable projection, Goldman Sachs anticipates gold prices could reach nearly $5,000 per ounce, particularly if policies perceived to undermine the Federal Reserve’s autonomy, such as those speculated under a potential second Trump presidency, are enacted.

The current global economic landscape is characterized by a pervasive sense of unease regarding national budgets and the capacity of central banks to effectively manage inflation in the medium term. European Central Bank (ECB) President Christine Lagarde and Vice-President Luis de Guindos, speaking in September 2025, acknowledged that while headwinds such as increased tariffs, a strengthening euro, and intensified global competition are currently dampening economic growth, their impact is expected to wane in the coming year. They noted that recent trade agreements have provided some measure of relief from uncertainty, but the full ramifications of the evolving global policy environment will only become apparent over time. Despite these challenges, the ECB remains committed to its objective of stabilizing inflation at its two percent target over the medium term.

Ugo Yatsliach, Founder of Gold Policy Advisor and a professor of economics and finance, articulates a core concern driving this reorientation: "Central banks aren’t just worried about inflation – they are worried about a world where dollar assets can be sanctioned, seized or devalued." He elaborates that this trepidation is leading central banks to pay a premium for gold, viewing it as a means to construct a "politically neutral, seizure-resistant reserve portfolio." The underlying vulnerability, according to Yatsliach, is an over-reliance on the US dollar. While US Treasuries and funding mechanisms continue to form the bedrock of many reserve portfolios, demand is demonstrably softening as competing economic blocs, the emergence of parallel payment systems, and the ongoing realignment of global supply chains erode the utility of fiat reserves and introduce complexities into monetary policy formulation. Consequently, in an environment rife with geopolitical and economic uncertainty, gold is increasingly perceived as an indispensable hedge—a strategic safeguard against systemic risks and a buffer against the potential weaponization of financial assets. Industry observers characterize this as a fundamental structural shift in the global flow of capital.

The Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF) concurs, positing that recent geopolitical events have created a fertile ground for gold to reclaim its prominence within central bank reserve portfolios and even serve as a medium for international settlements for certain nations. Earlier in 2025, reports indicated that central banks collectively acquired 410 tonnes of gold in the first half of the year, a figure 24% above the five-year average. Emerging market economies were at the forefront of this diversification away from dollar reserves. Financial advisors are now recommending that investors allocate between five and ten percent of their portfolios to gold, either through direct bullion holdings or exchange-traded funds (ETFs), as persistent geopolitical risks, coupled with potential dollar strength and policy shifts, present ongoing short-term volatility.

A spokesperson for the ECB, when contacted, confirmed that "the ECB holds gold as part of its foreign reserves, and we recognise its historical and strategic significance in reserve management." However, like many other central banks, they declined to comment on specific market forecasts or the policies of other monetary authorities.

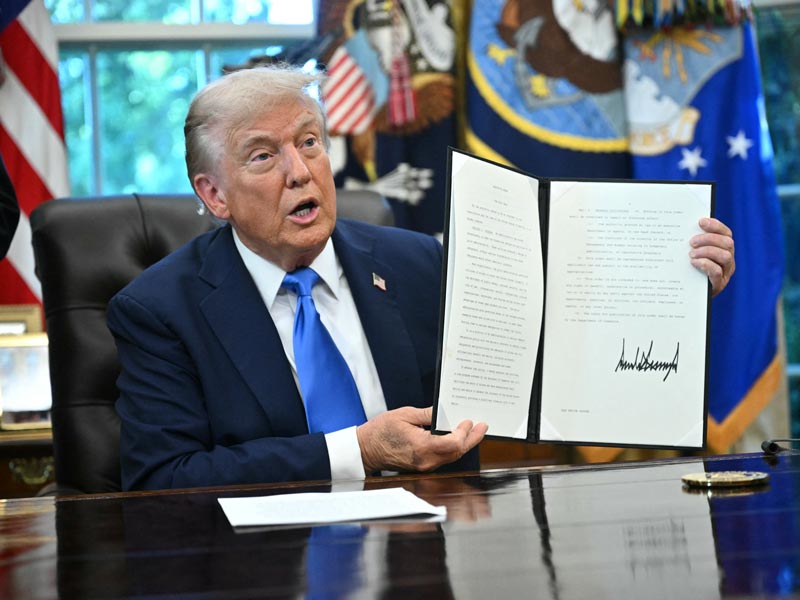

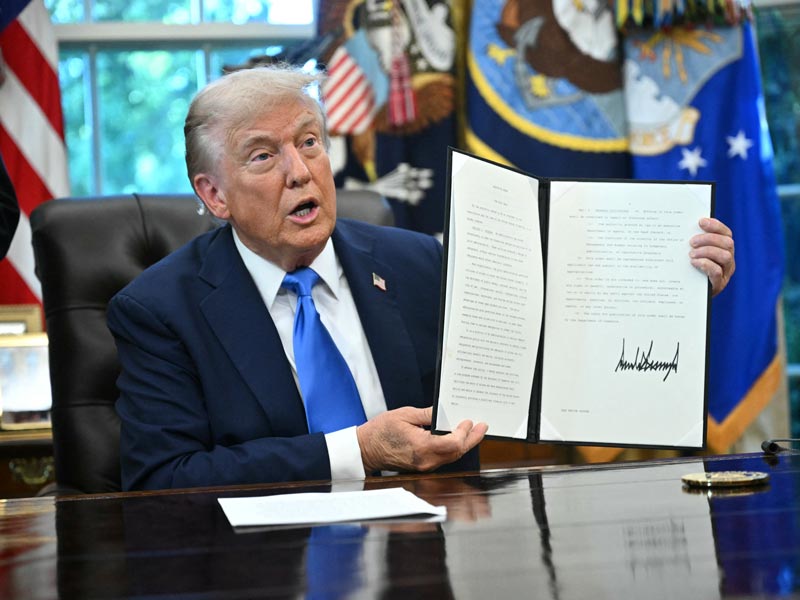

Hugh Morris, Senior Research Partner at Z/Yen Group, finds the current level of institutional interest in gold particularly noteworthy. He observes a "definite reversal of an historic trend, because up until recently central banks have been net sellers rather than net buyers of gold." He attributes this pivot, in part, to the perceived disruption caused by President Trump’s policies, which have accelerated concerns about an over-dependence on the US dollar. These anxieties, while predating the Trump administration, have been amplified, prompting a re-evaluation of reserve diversification strategies.

Furthermore, the global security environment has demonstrably deteriorated, marked by an increase in conflicts and crises, such as the ongoing wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. Gold, historically a reliable hedge against economic shocks and volatility, is once again being recognized for its intrinsic stability, offering a level of certainty absent in many other asset classes. Morris also points to a psychological element, a form of "groupthink," where observing other central banks actively accumulating gold encourages a herd mentality, ensuring that institutions can justify their own acquisitions if questioned by politicians or peers.

For developing countries, the allure of gold is particularly pronounced. Michael Bolliger, Chief Investment Officer Emerging Markets at UBS Global Wealth Management, highlights that emerging market central banks are actively seeking assets that exhibit lower correlation with the US dollar and are less susceptible to interest rate fluctuations. This ongoing accumulation is expected to continue, as these institutions often prioritize gold as a stable store of value over short-term price sensitivity.

Bolliger further attributes the recent surge in gold prices to several key factors. Anticipation of further interest rate cuts by the US Federal Reserve, coupled with persistent inflation, has driven real interest rates lower in the United States, making gold a more attractive alternative to interest-bearing assets. The expected easing of Federal Reserve policy has also contributed to a weakening US dollar, thereby enhancing gold’s appeal for non-dollar investors. This demand is further bolstered by robust investor interest, evidenced by rising ETF holdings and substantial central bank purchases, which collectively support elevated price levels. Despite a brief summer slowdown, these underlying drivers, amplified by heightened geopolitical risks and policy uncertainties, have propelled gold to new record highs.

Morris also notes a fascinating divergence from historical patterns: the long-standing inverse relationship between gold prices and interest rates appears to have broken down. Traditionally, higher interest rates correlated with lower gold prices. However, the current environment features relatively high interest rates coexisting with soaring gold prices, both driven by a heightened perception of global risk.

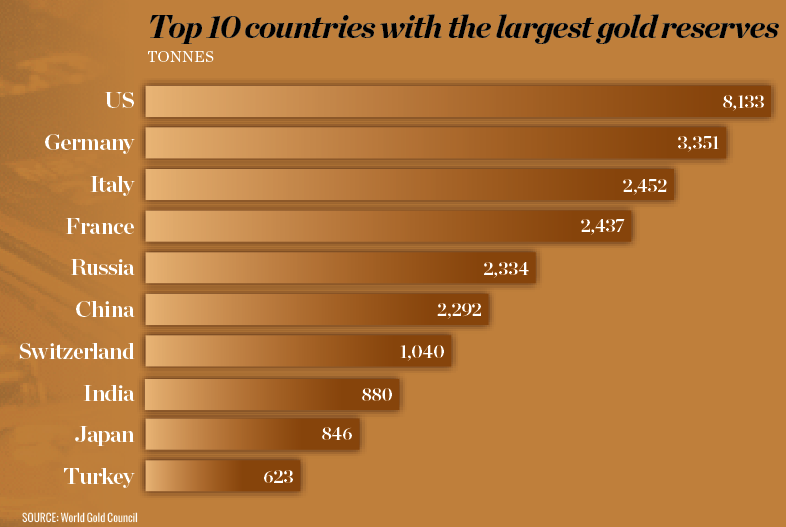

Eric Strand, Portfolio Manager of the AuAg Funds, suggests that while the Bank of England and the European Central Bank have been relatively less active in gold acquisitions, China and other Asian central banks have been significant buyers. He notes that Poland, for instance, has begun to actively increase its gold reserves, acting in response to perceived systemic vulnerabilities. In contrast, he posits that historically, the Bank of England has tended to divest gold at inopportune moments. China and Russia, as major gold producers, naturally retain their output for reserve enhancement. Strand also casts a skeptical eye on the US gold reserves, particularly in light of President Trump’s stated desires to re-evaluate them, and questions persist regarding the exact quantities held at Fort Knox. He points out that the US held significantly more gold post-World War II and that substantial portions were transferred to Europe during the post-war reconstruction period. This, he argues, contributed to the eventual decoupling of the dollar from gold in 1971 under President Nixon, marking a pivotal moment in the global monetary order. Since then, all fiat currencies have been tied to the dollar, which, when measured in gold, has experienced a dramatic decline in value.

The devaluation of fiat currencies is a systemic issue, exacerbated by quantitative easing (QE) programs where central banks can double currency volumes, effectively halving the value of each unit. The burden of servicing sovereign debt, especially in countries like the US with significant deficits, adds another layer of pressure. Strand suggests that the escalating cost of debt servicing, including defense spending, will inevitably compel a return to much lower, potentially zero, interest rates. He believes the Federal Reserve is currently lagging behind other central banks in this regard and that a move towards lower rates is unavoidable for debt servicing purposes. The prospect of the Fed re-engaging in QE to lower long-term rates, however, generates market apprehension due to its inflationary implications, further strengthening the case for gold as a hedge.

Nicky Shiels, Head of Research and Metals Strategy at MKS PAMP, emphasizes that confidence in traditionally safe assets like fixed income has eroded significantly due to extraordinary debt levels in most Western nations. This necessitates a reassessment of investment strategies, including a potential departure from the traditional 60/40 portfolio allocation and a turn towards assets such as gold, cryptocurrencies, or real estate. She cautions, however, that the universe of truly safe haven assets is contracting.

Morris attributes the current shift in capital flows to a perception that global risks are outweighing market opportunities. He explains that companies historically seeking high-growth, high-value investments, particularly in emerging manufacturing sectors, are now facing headwinds from US tariffs. This forces investors to re-evaluate their risk-reward calculations. The underlying philosophy of "Trumponomics," he suggests, is rooted in a zero-sum worldview where perceived opportunities are finite, and gains for one party come at the expense of another. This contrasts sharply with classical economic theory, which posits that a larger share of a growing pie yields better results than a larger slice of a shrinking one. This "win-lose" outlook, Morris argues, dictates policy decisions.

While some analysts focus on current political dynamics, others point to the "weaponization of the US dollar" as a more fundamental catalyst. Lobo Tiggre, CEO of Louis James, cites the sanctions imposed by the Biden administration in response to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine as a pivotal moment that resonated globally, signaling a new era of financial leverage. He asserts that this action, even prior to any potential second Trump presidency, underscored the inherent risks for nations entrusting their financial stability to the US. This, he contends, represents a significant step towards the erosion of the Bretton Woods accord, and Trump’s ongoing trade disputes further incentivize central banks worldwide to diversify away from the USD and US Treasuries.

Yatsliach frames this as a migration of capital from "yield at any cost" to "resilience at all costs." He observes that declining demand for US Treasuries, dollar devaluation, and escalating geopolitical tensions are collectively rendering paper assets increasingly risky, driving financial institutions towards gold for protection. The appeal of gold intensifies when its store-of-value function supersedes its role as a medium of payment. Gold’s liquidity outside any single sovereign’s control, coupled with a growing and more consistent share of official demand compared to a decade ago, underscores its enduring significance. "When capital stops chasing yield, it runs to permanence – and permanence is gold," he concludes.

China, historically a major holder of US Treasuries, has demonstrably reduced its holdings from $1.3 trillion to $765 billion since 2011, concurrently bolstering its gold reserves. This strategic move is aimed at diversifying its reserve portfolio and mitigating the risks associated with the potential weaponization of the US dollar. Regarding the US Federal Reserve, Yatsliach notes that the global community perceives an increasing effort by the US executive branch to exert influence over the Fed’s governance. This heightened political involvement fuels the perception of the dollar being used as a political tool, thereby accelerating the flight to gold, which is inherently politically neutral. Politics, in this context, acts as an accelerant for an ongoing diversification trend.

Morris concurs that President Trump is actively seeking to reshape the global financial and economic order, both domestically and internationally. He asserts that Trump is applying sustained pressure on the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates to stimulate economic activity. This strategy, however, raises concerns among other central banks, who fear that aggressive rate cuts could exacerbate existing inflationary pressures within the US economy.

Yatsliach comments that "Social media isn’t wrong, US policy is shifting." He emphasizes that the critical factor is how these US policy shifts are transmitted globally through the US dollar, Treasuries, and financial markets. He explains that any executive attempt by the US government to influence the Fed’s governance and policy decisions, through appointments or high-profile disputes, generates significant uncertainty in global markets. The overarching fear is that the President could wield excessive power over the dollar, the linchpin of the global reserve system, transforming it from a market-driven asset into a political instrument.

He further highlights a lesser-known aspect of US financial history: the Gold Reserve Act of 1934 transferred ownership of all gold from the Federal Reserve to the US Treasury, establishing the Exchange Stabilisation Fund (ESF) with the mandate to control the dollar’s international value. Section 10(a-c) grants the President and the Secretary of the Treasury broad discretionary powers over gold and foreign exchange transactions, operating the ESF. Crucially, the act stipulates that these actions are final and not subject to review by other US officials. Therefore, if a president were to succeed in removing a sitting Fed Governor and appointing individuals amenable to executive influence, the global monetary system could become susceptible to unprecedented executive control from the US.

This scenario would diminish the independence of the Federal Reserve, making it vulnerable to the political agenda of the prevailing administration. Consequently, foreign central banks would likely increase their reliance on self-insurance mechanisms. While central banks may not fear individual presidents, they do fear the politicization of the dollar, which could lead to increased volatility in dollar funding. This poses a critical concern for non-US banks, such as the Bank of England and the ECB, which often borrow in dollars and rely on the Fed’s swap lines for stress support.

Yatsliach warns that if the US relaxes its oversight and faces financial turbulence, contagion can spread rapidly through derivatives, repo markets, and clearing networks into Europe. For the ECB in particular, volatility in core interest rates and the dollar can complicate monetary transmission mechanisms and reignite fragmentation risks within the Eurozone. Tariffs, he explains, can directly impact yields, the dollar’s value, and risk premia, thereby affecting the value of other central banks’ dollar reserves. When the anchor currency appears politically compromised, gold emerges as the universal insurance policy for every central bank.

Can gold, therefore, provide a more resilient hedge against geopolitical and economic risks than the US dollar and Treasury bonds? Morris argues that these assets are fundamentally disconnected. Gold, he asserts, is inherently an asset for times of uncertainty. He anticipates that bonds and other interest-sensitive instruments will continue to offer premium returns due to the elevated levels of global risk and uncertainty, but independently of gold’s price movements. "Currently, we are seeing high interest rates and a high price for gold, both driven by the levels of risk and uncertainty in the world, but independently of each other," he elaborates.

Bolliger corroborates this by highlighting that gold has outperformed many other asset classes, including the US dollar and US Treasury bonds, in recent years. "As long as investors remain preoccupied with geopolitical concerns as well as political and policy risks, we think gold can continue to outperform safe haven assets such as the US dollar and US Treasury bonds," he states. He does, however, caution that gold prices can also experience fluctuations during "risk-off events as investors liquidate assets and hide them in (US dollar) cash."

Regarding the Goldman Sachs prediction of gold potentially reaching $5,000, Strand suggests that prices below $4,300 appear undervalued, particularly considering the current deficit and sovereign debt situation. While he acknowledges that $5,000 sounds high, it represents only a 25% increase from $4,000, and he is confident that gold prices will continue to climb. He anticipates that the Federal Reserve will inevitably be compelled to lower interest rates, a move that would further propel gold prices. Consequently, he views the Goldman Sachs scenario as realistic, with the pace of central bank money printing and QE measures playing a significant role. Ultimately, as long as uncertainty persists, investors are likely to continue flocking to gold.